My 2nd great grandparents, Charles Joseph Gordon Logie and Rosa Clara Friedlander Logie, were both born in England. Both lived in London as a child, yet they met for the first time at Sydney, Australia. After traveling almost completely around the world, they spent most of their lives in Utah.

My 2nd great grandparents, Charles Joseph Gordon Logie and Rosa Clara Friedlander Logie, were both born in England. Both lived in London as a child, yet they met for the first time at Sydney, Australia. After traveling almost completely around the world, they spent most of their lives in Utah.

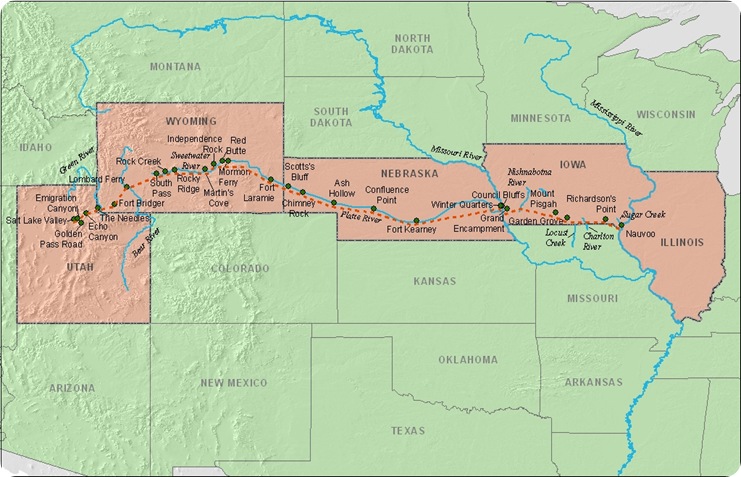

In Sydney, the Mormon Missionaries taught them the Mormon faith. When Brigham Young called for Mormons to gather to Utah, they left for that destination. The story of their eastward journey by sea contrasts with the story of the westward toiling handcart companies, which came to Utah at about the same time. The same courage and the same faith sustained them both.

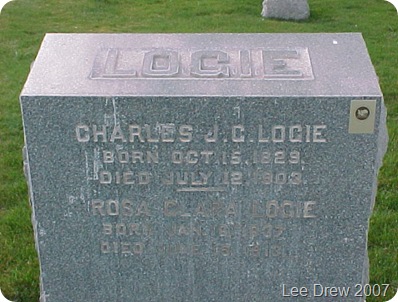

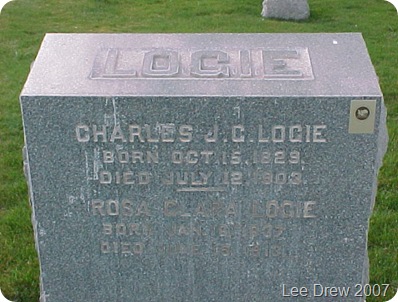

Charles Joseph Gordon Logie was born in Chelsea, Middlesex Co., England on 15 October 1829, to Charles Hook Gordon and Ellenor Chalan Logie.. The following account of his fathers life was published in a New Zealand newspaper: "Logie, Charles Hook Gordon, born in London 1810, landed at Sydney 1839, and took charge of government stores at Auckland 1840; was present at the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi; landing surveyor at Wellington; Sub-collector Shand, arriving 1852 with wife and family. Walked to Dunedin twice a week to transact business, and on one occasion, night coming on, lost his way in the brush and spent the night somewhere about Upper Junction; acted as postmaster, receiver of land revenue, chief gold receiver, harbor master, comptroller of navigation laws, Sub-Colonial Treasurer, and was also lay reader in connection with the Anglican Church both at Port Chalmers and Dunedin. Mr. Logie and one of his sons erected the first custom-house at Bluff on its being declared a port of entry, and the building is said to be standing to this day. Made the journey overland to Invercargill to establish an overland mail service, continued for some years, Jack Graham being the postman. Rev. W. Bennerman accompanied him back and they missed their way on the Mataura  Plains. He died September 19th, 1866 in Dunedin."

Plains. He died September 19th, 1866 in Dunedin."

The biographer neglected to mention that he lived to tell of his adventures on the Mataura Plains, and died at home. However, the main story is of the oldest child, Charles Joseph, who was ten years old when his father moved the family to New Zealand. He shared the adventure of being lost about Upper Junction and helped build the custom house at Bluff. New Zealand was then in the early stages of settlement. A few hardy souls had bunched together near the coast in various villages. Natives were still a menace and the inland plains were wild.

Ten years after the Logie’s arrival, James MacAndres became interested in Otago. On his arrival in 1851, he began to make business concerns more mature. MacAndres, building on the foundation of government machinery already set up, helped build lime kilns at Kaikorai, a flour mill at Green Island, and started a shipment of trade. He sent wool to London in his ships and brought back colonists. He also established contacts with Sydney and Melbourne, Australia, which were already sizeable towns.

By 1880, the little province of Otago, abolished as a separate unit of government by the United Government earlier than this date, had not only high schools, but also a university which could grand degrees. Schools were established early in all the colonies and Charles Joseph attended those at Nelson. He, with his father, saw much of the work being done to improve harbors, establish postal service, and bring settlers to the country and sell land to them.

Charles’ father believed that no man was educated until he had served his apprenticeship at sea and became an able-bodied sailor. When Charles became 18, his father, then sub-collector at Nelson, New Zealand, sent him to sea. Charles never returned to New Zealand, nor did his two younger brothers who were sent to sea in their turn. The still younger brothers, who  followed several girls in the family, did not receive this part of their education. Of the three brothers, one settled in Australia, another was lost at sea and Charles, who was seaman about the colonies for seven years, did not return to Nelson because Sydney was his home port. He met a Mormon girl in Sydney, Australia. This girl, Rosa Clara Friedlander, was born on the island of Guernsey, located off the coast of France, on 15 June 1837 of French-English and German Parents. When she was still a child, shortly after her brother James was born, her father died. Her mother moved to London, where she worked at her trade of dressmaking.

followed several girls in the family, did not receive this part of their education. Of the three brothers, one settled in Australia, another was lost at sea and Charles, who was seaman about the colonies for seven years, did not return to Nelson because Sydney was his home port. He met a Mormon girl in Sydney, Australia. This girl, Rosa Clara Friedlander, was born on the island of Guernsey, located off the coast of France, on 15 June 1837 of French-English and German Parents. When she was still a child, shortly after her brother James was born, her father died. Her mother moved to London, where she worked at her trade of dressmaking.

The colonies were well advertised in London. Otago, New Zealand had a London branch of the Lay Association of Scotland for promoting the settlement of the colony of Otago. Similar agencies from a large number of the settlements of the colony were collecting colonizers. Rosa's mother accepted the job of going, as matron, on a vessel bound for Sydney. She made her home in Sydney when Rosa was 12 years old. Work for women was plentiful. The men in London, who sought women to go to Sydney, hardly exaggerated the opportunities.

Rosa's mother soon married a miner named Watson who became quite wealthy. They early became interested in the Mormon missionaries teachings. They were taught by Elders John S. Eldridge and James Graham, who were at the time under Bro. Farnham, President of the Mission House.

Rosa walked some distance to attend services with her friend Sister Mary Ann Evans, newly married to Robert Evans. On the porch of this Mission House, Rosa Clara Friedlander met Charles Joseph Gordon Logie. He was baptized, after missionary C. W. Wandle had explained the faith to him in April, 1853.

On 24 May 1853, Rosa Clara Friedlander, then nearly 16, and Charles Joseph Gordon Logie, then 24, were married. Because the Australian government would not allow Mormon Elders to perform marriages, they first walked several miles into Sydney to the Church of Scotland chapel and were married by a priest. They then walked back to the Mormon Mission Presidents home where he performed another marriage ceremony.

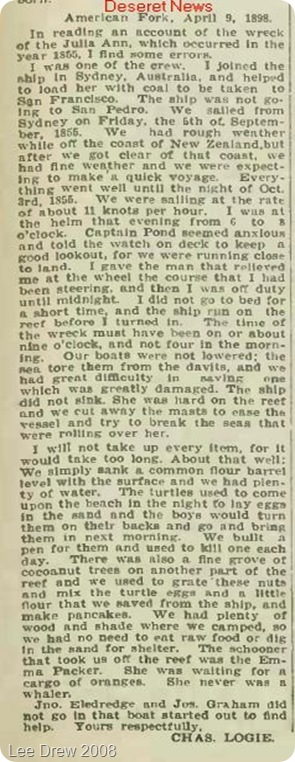

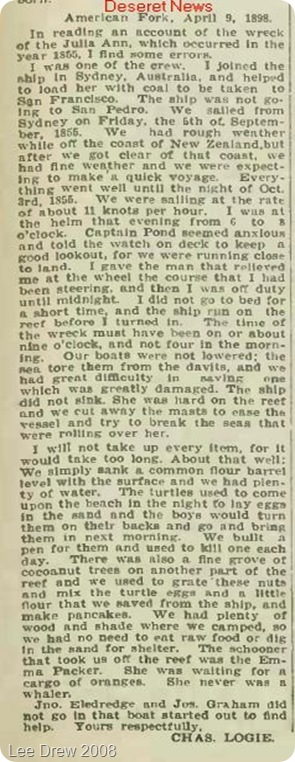

Nearly all of this faithful little group of Mormons came to Utah when the missionaries returned at the call of the church for all Mormons to gather in Utah. Sister Mary Ann Evans and Brother Robert Evans left earlier than the Logie’s and this made them all the more anxious to leave the next year, shortly after their baby Ann was born. They took passage on the "Julia Ann" bound for San Francisco with Charles working on the ship as a steersman to pay for part of their passage.

Bro. John S. Eldridge sailed on the same boat and the sailors grumbled that the ship would never reach port with both women and parsons aboard. That did not prevent the "Julia Ann" from sailing with both women and Mormon missionaries among her 23 passengers. The weather was perfect and the ship was well manned, yet it did not reach port.

Bro. John S. Eldridge sailed on the same boat and the sailors grumbled that the ship would never reach port with both women and parsons aboard. That did not prevent the "Julia Ann" from sailing with both women and Mormon missionaries among her 23 passengers. The weather was perfect and the ship was well manned, yet it did not reach port.

A short time after dark and a few days out of port, the ship struck a coral reef off the Scilly Island, one of the Society Group. The night was clear and the weather fair, but the ship was a little off course. The men below felt the shock and scrambled to the deck wearing the first thing that came to hand. The Captain realized that nothing could be done to save the ship. She would soon be battered beyond repair on the rocks.

A sailor swam through the surf to an out jutting rock and fastened a rope to it. They then attached a sling seat to the rope. Bill Williams, a sailor, saved seven women, taking them one by one on his lap as he sat in the sling. He could rest, but in order to make progress, he had to brace with one hand grasping the rope with the other. All were taken to the rocks and stood in water to the waist at high tide until morning.

Little Ann went about fastened securely with a shawl to her fathers back. The next morning, they followed the coral reef around to a small bay on the main island. The island was barren and rocky, without any vegetation.

The work of rescuing included little more than the saving of all of the passengers, some of whom were scantily dressed.

Charles Logie found he had on Billy Williams shoes, but Bill Williams refused to take them back. Bro. John Eldridge was also a barefoot man. A tool chest was saved by one of the sailors and one of the women’s trunks was washed ashore. An Irish sailor tried to hide a barrel of biscuits he had found along with a chest of tea that was washed ashore. He was discovered and the biscuits were used by everyone. Enough wreckage was saved that the men were able to build a small boat with the rescued tools. The boat made the dangerous three mile trip to a neighboring island, where a few coconuts were found.

The women made shirts for the men from dresses from the trunk and made bandages for sore feet. The only food on the island was turtles and turtle eggs. Water was caught in a reservoir that had been dug in the rocks. A large share of the tea and coconut milk went to Ann via her mother who got all the best of things, including a silk petticoat tent. They had all the turtle meat and eggs that anyone wanted. After more than two months of this life, they decided that some of the sailors should go in the boat and try to reach a lane of sea traffic to hail a ship. They made the venture and brought the "Emma Packer", a French fruiting vessel, to the rescue. After three long months on the desolate island, on which a Mrs. Andrews and her children died of exposure, all but these three arrived safely at Tahiti, less than half way to their goal.

The Logie’s remained seven months at Tahiti until they could arrange passage to San Francisco. They found friends everywhere and stayed for a time at the Mormon mission and among the Mormons in San Francisco. Upon arriving in San Francisco, the sailors gave Rosa Logie a pewter teapot and a Mrs. Spanzenburg and Betty Austin gave them dresses for Ann.

Ann remembered wearing them in later years in American Fork, Utah, because they were nicer than those worn by the other girls. They parted from these friends in San Francisco to take charge of on of John C. Nailes ranches in Carson Valley, Nevada.

On this ranch, they worked for shares, putting in crops of vegetables and caring for a dairy herd. They churned butter with the power of a water wheel made by grandfather Logie. Food was in demand and the prices were considered high, even by the gold miners in California. The miners had no time to farm, but had gold to pay for food. They sold part of their crops to raise cash for other living necessities.

On the Carson Valley ranch, the Logie’s had a second child. It was a boy, who they named Charles Jr. Brigham Young issued a second urgent call for all who called themselves "Mormons" to come to Utah, or Deseret as they considered naming the state. The Logie’s left the ranch at Carson Valley and came over the mountains and desert in a Conestoga wagon to Utah. The wagon was drawn by army trained mules, both belonging to John C. Nailes. They settled on one of his ranches in Lehi, Utah. Lehi was at that time a walled town, and the men guarded the town against Indian attacks. The attacks were especially apt to occur in the winter time, when the settlers had food stored and the Indians were starving.

Grandfather Logie, walked the walls one night with a broomstick on his shoulder. He had loaned his revolver to a man going out hunting and fortunately for him, only his friends knew of the frightening circumstance. The Logie’s stayed that winter in Lehi within the wall. They went out to the John C. Nailes farm near Lehi in the summer and raised a crop of vegetables and hay.

They spent the next winter in Provo, Utah, where grandfather Logie worked with Silas Smith in the tithing office. He planned with some others to invest in a farm in Provo Valley and raise a crop the next summer. The cooperative was one of the first to be completely fenced and as usual, the Logie’s improved the house by some of his clever carpentry work when they moved in the home.

They spent the next winter in Provo, Utah, where grandfather Logie worked with Silas Smith in the tithing office. He planned with some others to invest in a farm in Provo Valley and raise a crop the next summer. The cooperative was one of the first to be completely fenced and as usual, the Logie’s improved the house by some of his clever carpentry work when they moved in the home.

The next march, another child, Silas was born in the farm home. Grandfather still worked at the Tithing office and made frequent weekend trips to the farm, where he had left his family. The place was very lonely for a woman alone with her children and Grandmother thought often of her old friends she had left in Australia. Sister Mary Evans was now living in American Fork, Utah. She and her husband Robert had come to Utah directly from Australia without the shipwreck or long stops and they were comfortably settled and owned a team and wagon.

Grandmother insisted on borrowing the team and moving to American Fork early the next spring. A shack on "Rotten Row", so called because the houses were so inadequate as shelter, served them until the next fall, 1860. They then bought a one room log house from Henry Boley. This room was later built around by other rooms and served as a middle room. They finally owned a home and they remained in it for the rest of their lives. John Eldridge also lived in American Fork and the first summer the Logie’s borrowed the Evans team to farm on John Eldridge’s farm. That winter, they lived in their own house and opened a carpentry shop.

Their home was always open to the wayfarer. There was not a hotel in American Fork at the time. Many people, both rich and poor, found haven in their home. Travelers to conference driving through the country made it their stopping place. They drove their oxen in the yard and made a camp. Many a bed was made on the floor. Charley Green once made a bed of coats on the dining room table.

Stephen L. Chipman, a very good friend, boarded with Charles and Rosa for a time. He said "the meals were always clean, well cooked and enjoyable. It was not the meals alone, but the wonderful welcome you were always sure of at the Logie House that made you want to go there."

Charles Logie was a happy man and always enjoyed a good joke. His eldest daughter said the first she could remember of her father was when he'd get up in the morning and light the fire. He would then whistle and dance the sailor horn pipe dance to wake them up. He was their alarm clock. He continued to do this most of his life. When Stephen L. and Zina Nelson Chipman were newlyweds, Charles being a carpenter, was asked to make the screens for the windows and doors of their first home. Bustles were worn by the ladies in those days and no lady was seen without one. Zina had one made of white silk to match her wedding gown. Come Sunday morning, she couldn't find it and said she had to go to church disgraced.

During church, Stephen put his hand in the pocket of his frock coat and there was the lost bustle. Charles had seen it on a chair in the bedroom and had tucked it in his pocket as a joke. Zina said "I'll always hold that against him."

Grandfather loved to work on framing houses and in furniture polishing. He kept an account book telling all of his work and the amount he was paid for each project. It tells a great story about his life. Almost every home in the community had pieces of his handiwork in it. He also made most of the coffins used in the north end of the valley. Farm produce was accepted for payment in place of money. In good potato growing years, potatoes piled up, and in good apple growing years it was apples and so it went. He built the first flag pole in American Fork, so the account book says and he mounted the City Park Bell, which he was commissioned to ring every night at nine o'clock.

For a time, he incorporated with Ted Lee, a painter, James Clark, Jack Bennett, James Carter and Reuben Broadhurst, all general carpenters with their own minor specialties. They took jobs together, set a price for each of their services, and then put up houses much more quickly than alone. The homes benefitted form each of their specialties. They built the American Fork Ward Chapel, now Science Hall at the Harrington School. Furniture came in straight pieces and only grandfather liked to assemble them.

The others were often asked to do work in their specialty and when one team member was gone, the others suffered.

The plan worked in theory, but unfortunately, the working arrangements did not work out. They also could not agree about having joint capital invested in lumber and furniture. The men parted friends, and turned back to their individual businesses and bookkeeping.

Shortly after they settled in American Fork, the coming of Johnstons Army caused quite a disturbance. Resistance took the form of hectoring the army. Wagons were burned and mules were driven off, roads were flooded and at Echo Canyon a force assembled but then disbanded. A. S. Johnston brought his army to Camp Floyd despite these minor irritations and people in American Fork found them profitable neighbors. All sorts of farm products from butter and eggs to vegetables were sold at the camp and even bits of fancy work and embroidery were sold. Grandmother made some things that brought good prices, having learned many sewing skills from her mother. The Civil War broke out and Johnston left with his men. Johnston was a Southerner and went to fight for the South. The supplies left at Camp Floyd soon disappeared. Gossip said that a couple of boys, who sold buttermilk to the army found the camp deserted.

They helped themselves to enough groceries to start a store on Main Street. Grandfather Logie went to the camp and collected all the candle stubs from the barracks, found a broom, and brought home the back door that he put on their house. The candles were the first spern candles they had seen. They were used to melting candles with a floating wick. A large number of the community shared in the dismantling of the camp. The store on Main Street sold hams and bacon at prices higher than most could pay. Food was so precious that any waste was a crime to be punished by the severest penalties.

The government property at Camp Floyd was felt to belong to everyone, so each tried to get his share and blame those that took more than they needed for themselves. Prices for food was very high at this time.

Although money was scarce, food problems seldom worried the Logie’s. They received food for their work and Grandfather paid his tithes by working one month in ten on the Temple Square Buildings in Salt Lake City. Little money was needed to buy clothing and to pay taxes. He earned this money in later life by making coffins, lining and all, for $1.50 to $4.50 each. His most expensive coffin sold for $20.00 He provided both the coffins and the undertaker services in American Fork until the Anderson family started a funeral home.

Although money was scarce, food problems seldom worried the Logie’s. They received food for their work and Grandfather paid his tithes by working one month in ten on the Temple Square Buildings in Salt Lake City. Little money was needed to buy clothing and to pay taxes. He earned this money in later life by making coffins, lining and all, for $1.50 to $4.50 each. His most expensive coffin sold for $20.00 He provided both the coffins and the undertaker services in American Fork until the Anderson family started a funeral home.

In addition to being the town undertaker, Charles also built the fence around the American Fork City Cemetery.

Granddaughter Laura Logie Timpson liked to go to his shop and watch him work. He saved her the pieces of brocaded velvet from the caskets. She made many a pretty doll quilt and hat of them, but had to keep them hidden away from her mother who did not like to see them.

Charles was very superstitious and would never start anything on Friday. He was very fond and very kind to animals and made great pets of them. He owned a beautiful bay horse, "Bill." He washed and wiped him dry every week. The horse met every visitor as they came to the gate. One day a boy came who "Bill" didn't recognize and with his teeth, he picked him up by his collar and lifted him back over the fence.

He also had a brown curly haired dog named "Jod." He buried "Jod" in a little coffin when he died. He had a bantam rooster "Dick" that perched on the bench in his shop and watched him work. Charles talked to him as if he was a child. Dick never let Rosa in to bother Charles. If Charles didn't want to go do something, he would say, "Get after her Dick." The rooster would fly at Rosa's head until she was glad to run for the house. Charles would then laugh until he cried. He was always laughing and singing at his work. He wasn't a public man, and was very quiet and unassuming, but was always a good neighbor and faithful friend.

Charles was ever loyal to England and Queen Victoria. He would not take out U.S. citizenship papers until after her death. Charles and Rosa were married three times. First in Australia,(twice the same day), second on board ship by a Mormon Elder and later in the old Endowment House in Salt Lake City.

Charles was ever loyal to England and Queen Victoria. He would not take out U.S. citizenship papers until after her death. Charles and Rosa were married three times. First in Australia,(twice the same day), second on board ship by a Mormon Elder and later in the old Endowment House in Salt Lake City.

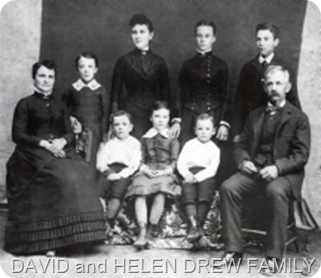

At the time when polygamy was very predominate and the authorities advised the brethren to take another wife, Charles mostly looked in fun at several girls. He would suggest a name to Rosa saying "Rosa, what do you think about her? Will she do?" Rosa would bat her eyes and pretend to think and then say, " No, Chasler, I don't think she'd fit." Needless to say, they never found one to fit. Grandfather and Grandmother Logie had 12 children. All were brought up in the Mormon faith. The missionaries in Sydney did their work well when they explained the faith to the sailor lad. It blossomed into a beautiful life of faithful service to the Lord.

Rosa Clara Friedlander Logie was born on the Isle of Guernsey, in the English Channel on 16 June 1837 of English, French and German descent. Her father, Henry Friedlander, died when she was a small child. Her mother, Eliza Sampson Friedlander, remarried a Mr. Watson in London, England. When Rosa was 12 years old, they went to Australia.

Rosa Clara Friedlander Logie was born on the Isle of Guernsey, in the English Channel on 16 June 1837 of English, French and German descent. Her father, Henry Friedlander, died when she was a small child. Her mother, Eliza Sampson Friedlander, remarried a Mr. Watson in London, England. When Rosa was 12 years old, they went to Australia. Large turtles came out of the ocean and crawled over them. They were too tired to get out of the way and every little while you could hear a thud or splash as someone flung off a troublesome turtle. There were also a few crabs around.

Large turtles came out of the ocean and crawled over them. They were too tired to get out of the way and every little while you could hear a thud or splash as someone flung off a troublesome turtle. There were also a few crabs around. Charles returned to Provo to work during the winter of 1860, leaving Rosa alone with 3 small children in Wallsburg. Indians often came in to get warm and would burn up all their wood. She was just tired of living up there alone, and one day she bundled up the children and started down Provo Canyon through deep snow. She met her husband coming up. They returned to their home, but planned to move to American Fork, which they did the following spring, living there the remainder of their lives.

Charles returned to Provo to work during the winter of 1860, leaving Rosa alone with 3 small children in Wallsburg. Indians often came in to get warm and would burn up all their wood. She was just tired of living up there alone, and one day she bundled up the children and started down Provo Canyon through deep snow. She met her husband coming up. They returned to their home, but planned to move to American Fork, which they did the following spring, living there the remainder of their lives.

James Hoggard

James Hoggard