My first cousin (six times removed), Major William Logie, had many interesting experiences in his life. One of the most interesting was being a passenger aboard the bark “Morning Star” when it was attacked by pirates.

A current day cousin, Robert Huggard of Canada and a descendant of William, sent me notes and articles about William and his family. William was married twice. His first marriage was to Mary McNair on the 16th of March 1808 in Skelmorlie, Ayrshire, Scotland. Six children were born into their family. Unfortunately, Mary died at the young age of thirty-four on 2 Aug 1818.

A current day cousin, Robert Huggard of Canada and a descendant of William, sent me notes and articles about William and his family. William was married twice. His first marriage was to Mary McNair on the 16th of March 1808 in Skelmorlie, Ayrshire, Scotland. Six children were born into their family. Unfortunately, Mary died at the young age of thirty-four on 2 Aug 1818.

After four years, William married Anne Smith, on 2 February 1822 in Banff, Banffshire, Scotland. Anne was a thirty-eight at the time and had been born in Gamrie, Banffshire.

William’s military assignments took the family around the world. Before leaving for their greatest adventure, a son, Alexander was born on 16 December 1823 in Rosefield, Nairnshire. Scotland. Two years later, a daughter, Barbara was born on 31 Jul 1825 aboard ship on the way to Ceylon.

A member of the Gordon Highlanders, William was assigned as the senior British military representative to Ceylon early in 1825. All of their children were left in Scotland rather than taking them on the long arduous journey around Africa and back up to Ceylon. However, on the 31st of Jul 1825, a daughter, Barbara, was born aboard ship.

After completing the assignment the Logie’s embarked on their journey home aboard the ship Morning Star. Unfortunately, it was attacked by pirates with devastating results.

We enter the story of piracy, survival and valor at this point:

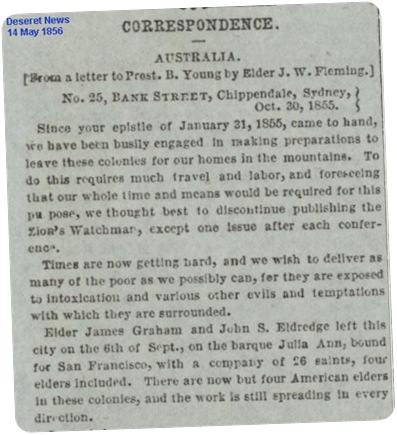

The Bark, “Morning Star”, Thos Gibbs, Commander, sailed from Colombo on 13 Dec. 1827 with a cargo of coffee and cinnamon. The passenger list is below the following text. The principal passenger was Major William Logie, a Senior Military Representative to Ceylon, and his family.

The ship sailed from the Cape of Good Hope on 28th Jan'y 1828 and made the Island of Ascension at daylight on the morning of 19 February. 1828. The following is an extract form the Ship's Log Book date 19th Feb'y 1828.

"At daylight saw the Island of Ascension bearing west, distance about six leagues and saw a brig about 6  miles astern apparently in chase of us, which at 7 o'clock fired a fun and hoisted a Blue British Ensign. We then hoisted our colours and continued our course, under a press of sail, thinking on the appearance of the Brig that she vas a Privateer. About 8 o'clock A.M. the Brig coming up with us fast, fired two more blank shots, and being now nearly abreast of us, she fired a shot, which passed close to our stern, hauled down the British Ensign.

miles astern apparently in chase of us, which at 7 o'clock fired a fun and hoisted a Blue British Ensign. We then hoisted our colours and continued our course, under a press of sail, thinking on the appearance of the Brig that she vas a Privateer. About 8 o'clock A.M. the Brig coming up with us fast, fired two more blank shots, and being now nearly abreast of us, she fired a shot, which passed close to our stern, hauled down the British Ensign.

They hoisted Buenos Aryan colours and fired another shot, which fell short. We then shortened sail and the Brig hailed us and desired us to lav to, and send a boat on board, But was answered we had no Boat that would swim, on which she fired a round of Grape shot, which wounded one man, and did considerable damage to the sails main rigging. We then lowered the boat down, and the Mate with 3 hands and Hr. Smythe a passenger went in her. As soon as the boat got alongside and Mr. Smythe had gone on Board they ordered two of the men out of the boat and asked him if he was the Captain and had the ships papers, which being answered in the negative, they began beating them with their swords ordering them to return to the ship and send the Captain with the ships papers.

He accordingly went on board with the papers and the same boats crew, who were immediately ordered out of the boat and confined below. They then manned the boat with eight men armed with cutlasses and a long knife each. Boarding us, we could not oppose having no arms of any description. The few ships arms being perfectly unserviceable and the Brig laying within Pistol shot on the weather beam with her guns pointed. She appeared to carry 5 guns a side and one long battering gun on a traverse amidships.

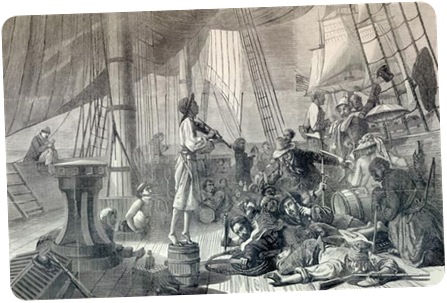

She was well manned, painted all black and sailed remarkably fast. As soon as they boarded, they began beating the people below with their cutlasses, severely wounding several. They then placed sentries on the hatchways and ran the ship into smooth water under the lee of the Island. They then cut away all the halyards and hove to. They then ordered the people from below and made them hoist out the skiff (the other boat having filled with water was cut adrift). This forced the people to work, beating them most unmercifully with their swords.

The Brig then sent her own boat on board with more men, and they commenced plundering the ship of the sails, cordage, the ships medicine chest, all the Captains live stock, the greater part of his wines and all the spirits and stores they could get at.

They also plundered the passengers of the greater part of their clothes, all their money and valuable articles they could find. They also broke open the hatchways and carried off everything they could conveniently take away.

About dark in the evening, they made all the males on board go down the fore hatchway, which they secured, and sent the women and children to the Cuddy. About midnight, the women, not being secured below, and hearing all quiet, ventured on deck and found they had quitted the ship and the Brig was out of sight.

They immediately gave information to the men, who with a good deal of exertion, cleared away as much as to allow them to get up onto the deck. It was found upon examination, that they had cut away all the Mission rigging and backstays, all the larboard main rigging and backstays and threw them with the backstays on the starboard side, together with the greater part of the running rigging. They had tried to cut away the mainmast and tiller, destroyed the Binnacle, and carried off the Company’s chronometer charts and long glasses. The ship had also been scuttled forward.

On sounding the well, she was found to have six feet of water in her hold. We then found that the Captain and Mate, two seamen and one soldier were missing. There remained only the Chief Mate, Carpenter, Cook, Steward and four seamen, and only three sergeants and eight soldiers (invalids) in any way fit for duty.

Every exertion was then made to pump the ship out and get the leak stopped, in which we happily succeeded by 6 o’clock a.m. We then set the foresail and kept her head to the northward, and at 9 o’clock, nothing in sight, set the fore-topsail, wind S.E. and steered W.N.W. We luckily found a spare compass, a Quadrant and two long glasses and some charts, which escaped their search.

Further extracts from the Log Book of the Bark “Morning Star” further tell the story of this adventure:

On the 22nd of Feb’y at 8 a.m. in consequence of the soldiers reporting that there was a very great heat coming up from below, they supposed the ship was on fire or there was a danger of it. All hands were set to immediately to hoist up the coffee and cinnamon from the fore hold. It was found that three lower tiers of coffee were wet and were heated and swelled to such a degree that a great part of the bags had burst. The heat was so intense that it was deemed necessary for the safety of the ship to throw overboard such bags as were in that state.

On the 22nd of Feb’y at 8 a.m. in consequence of the soldiers reporting that there was a very great heat coming up from below, they supposed the ship was on fire or there was a danger of it. All hands were set to immediately to hoist up the coffee and cinnamon from the fore hold. It was found that three lower tiers of coffee were wet and were heated and swelled to such a degree that a great part of the bags had burst. The heat was so intense that it was deemed necessary for the safety of the ship to throw overboard such bags as were in that state.

All of the loose coffee had to be thrown overboard as well. The remainder of the crew and the invalids who were equal to any exertion worked the whole day or until they were completely exhausted.

On the 23rd at 6 a.m., it was found necessary to continue throwing overboard more of the heated coffee, which was preserved in until about 6 p.m. On the 24th, the people employed as yesterday when it was found that the coffee stowed between the fore and main hatchways had swelled to the degree that it was found necessary to break out more bags to ease the ship.

On the 25th at 6 a.m., the people commenced taking out the two upper tiers of coffee so as to make a freer circulation of air from the fore to the after hatchway. They stowed it in the fore hold, which had been completely cleared of damaged coffee. The quantity could not be correctly ascertained, so much of it being loose, but it is supposed to amount to between two and three hundred bags.

The following passengers were aboard:

Major Logie, a Senior Military Representative to Ceylon

Barbara Logie, their daughter, born at sea in 1825

Mr. James Smyth, Merchant

Asst. Surgeon Goodwin

Hospital Asst. J. Johnston

Ordinance Clerk Wm. Robison

Helen Sloane

Pvt. E. Morris, Royal Artillery – severely wounded

Lieut. Wilkinson, Royal Staff Corps – time expired man

Pvt. Wm. Campbell – 16th Regiment

Pvt. Thos. Garvey – 16th Regiment – severely wounded by grapeshot

Pvt. Jas. McGreery – 16th Regiment

Pvt. Danl. Mullane – 16th Regiment – slightly wounded

Pvt. Hector McPhaddon – 78th Regiment – time expired – missing

Pvt. F. Finlayson – 78th Regiment – time-expired

Sgt. T. Martin – 83rd Regiment

Pvt. Pat Sloan – 83rd Regiment – severely wounded

Pvt. Henry Donohoe – 83rd Regiment – severely wounded

Pvt. John Moran – 83rd Regiment

Pvt. M. Bafferty – 83rd Regiment

Pvt. Wm. Walburn – 83rd Regiment

Sgt. P. Butt – 97th Regiment – of the Gordon Highlanders

Pvt. Thos Bangs – 97th Regiment

Pvt. Saml Lovel – 97th Regiment

Pvt. J. Painter – 97th Regiment

Women and children:

16th Ptc. 1 orphan boy

78th Mary Scott, widow 3 children

83rd Mary Martin 1 child

97th Anne Brett 1 child

Officers and Ships Company:

Thos. Gibbs – Commander – Missing

Geo. Burgby -- Chief Mate

Alex Mowat – 2nd Mate – Missing

H. Sales – carpenter – severely wounded

Pat Cullen – cook

Andw. Beyerman – steward

H. Johnson – seaman

M. Marlborough – seaman

Richr. Jones – seaman

John Vincent – seaman

John Larking – seaman -- missing

Rich. Hood Ritchie – seaman – missing

Jas. Smith, boy of the shipping master

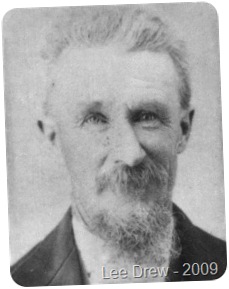

"Major William Logie was a Senior Military Representative to Ceylon 1825 - 1828. He was a major in the Gordon Highlanders, having joined the 92nd Regiment in 1800, transferred to the 97th Regiment as Captain, promoted to Major in 1808. He fought in the Peninsular War with Sir John Moore in 1809. He built a large stone house called "Glenlogie" (still is), 3 miles east of Kingston, Ontario. With his friends Sir John A. MacDonald and William Morris, he founded Queen's University, Kingston, Ontario, on the 18th of Dec 1839. His portrait has been donated to Queen's by Eleanor Mary James. An album of his sketches that he did while he was stationed in Ceylon has been given to the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto) by Mrs. James."

He was a Major in the 97th Regiment. Previously Captain in the Ninety Second Regiment, Gordon Highlanders.

William and his family were attacked by pirates while traveling at sea on a voyage from Ceylon to Scotland aboard the ship, 'Morning Star' in December 1827.

William along with his friends, Sir John A. MacDonald, William Morris, John Machar and others, helped found Queen's University in Kingston, Ontario, Canada

From the Lloyds' investigation into the piracy we are told that Captain Gibbs was killed by the pirates, and George Bushby (chief officer) took over command, had the holes in the hull repaired, rigged temporary sails, and got underway. They originally headed for the nearest port, Pernambuco, Brazil, but, after a conference with passengers Major Logie and James Smyth, it was decided that there was too much chance of running into other pirates off the Brazilian coast, and so they turned north towards England. On the 13 of March they met the English ship Guildford returning from China, and were given supplies, navigational instruments, and loaned two experienced sailors. The Morning Star arrived in London on the 18 of April, 1828, two months after encountering the pirates.

From the trial of the pirates we are also told that they were mutineers from a Brazilian slave ship El Defensor de Pedro, and, captained by the leader of the mutiny, Benito Solo, the commandeered ship attacked various merchant vessels in the Atlantic. The ship was then intentionally beached near Cadiz in Spain by Solo. All the pirates, except Solo and one other, were captured in Spain and sent to trial, with George Bushby (Chief Mate) and Andrew Beyerman (Steward of the Morning Star) acting as witnesses. A number of the pirates were hung, and the rest imprisoned. Benito Solo escaped to Gibraltar, but he was caught, tried and hung there. The other pirate was never found.

Statements by the Crew of the Morning Star

ADM1/2714 Charles Jones [Admiralty Solicitor's Dept.] to John Wilson Croker [First Secretary of the Admiralty] 1 August 1828, enclosing statements of witnesses.

Lancaster Place

1st Augt 1828

“I take the liberty to acquaint you that on the receipt of your Letter of the 29th Ulto inclosing two letters from Mr. John Bennett the Secretary of the Committee at Lloyd's relative to the plunder by Pirates of the Morning Star and communicating to me the directions of the Council [sic] to His Royal Highness the Lord High Admiral to endeavour to find out the witnesses and report whether they were likely to be able to establish the case against the parties in custody I immediately called upon Mr. Bennett and also Mr. Tindall the Owner of the Morning Star and made other enquiries with a view to find out the witnesses in question in which I have hitherto succeeded only as to two,Vizt Mr. George Bushby, the Chief mate and Mr. Andrew Beyerman the Steward of the plundered Vessel, whom I have examined and whose statements I beg leave to transmit herewith for the information of the Council to His Royal Highness, by which it will be seen that both of these witnesses not only can establish the Charge of Piracy, but are likely to be able to identify those of the Pirate Crew by whom the Morning Star was boarded and plundered and they have both expressed themselves willing to proceed to Cadiz, or elsewhere to give Evidence of the several facts stated in their Examinations and to speak to the persons of such of the Pirates as they had an opportunity of noticing.

I beg leave to add that Mr. Bushby is engaged to proceed on a Voyage to Madras as Chief mate of the same Vessel the Morning Star and that Mr. Beyerman is engaged as Steward of the Protector, Captain George Waugh which is expected to sail in the course of ten days on a voyage to Calcutta and they have intimated to me that if they are required to give up these engagemts in order to go to Cadiz they shall expect a full compensation for the loss that they must consequently sustain.

With respect to the other witnesses named in Mr. Bennett's letter of the 28 Ulto I find upon enquiry after them that Major Logie is supposed to be in Scotland; that Mr. John Johnstone is not to be found at the address furnished to me by the Owner; that Mr. Wm Robinson was during the whole Voyage and still continues in a state of mind approaching to insanity and that Mr. Goodwin was confined to his bed thro' illness during the Voyage, so that he could not have any opportunity of noticing the Pirates or their proceedings. - I have however some hope of being able in the course of a few days to find and examine Henry Sales the Carpenter of the Morning Star and Serjt Charles Wilkinson whom I propose in that case to examine but I beg leave to submit that from the circumstance of Mr. Beyerman being well acquainted with the French, Spanish and Portugueze languages which were spoken by the Pirates, he will be one of the most fit witnesses to send to Cadiz.

Herewith I return the papers sent to me on this subject.

I am Sir,

your most obedt hble servt

Chas. Jones

31st July

George Bushby, of Bothel, near Cockermouth, Mariner, at present residing at No. 18, Wade Street, Poplar , States -That he was lately Chief Mate of the Bark "Morning Star" of Scarborough of which Thomas Gibbs was Master on a Voyage from Colombo bound to London. That on the 19th of February last being about 3 leagues East of the Island of Ascension and steering North North  West they discovered about 7 A.M. a black Brig under British Colors six or seven miles astern which as soon as she saw the Bark began to fire Guns to bring her to, but the Bark continued to course until the Brig came within half a mile of her and then brought to after having had several shots fired at her which passed her - That when the Brig came up alongside she [illegible] hold down the English Colors and hoisted those of Buenos Ayres and some man on board her who spoke good English ordered the Bark to lower her topgallant sail and back her sails and to send a boat on board with the Captain and his papers -they complied with the ordered to back the sails but the Captain answered that he had not a boat on board which could swim, upon which some canister shot from a long gun were fired at them from the Brig which spread fore and aft from the water's edge to the Mast head, whereby a passenger, Thomas Garvey a private of the 16th Regiment was severely wounded, the foretopmast back stays, the foretop gallant back stay, the foretop mast stay, the foretop gallant rigging and the main Royal stay were shot away, and nine shot went through the foretop sail, two in the fore mast, and many shot went into the Starboard side of the Bark and through the Boats, upon which the Bark immediately lowered her Boat and Alexander Mowatt, 2nd Mate, Mr. James Smith, a Passenger, Henry Johnson, Joseph Marlborough and John Barking, seamen, went to the Brig to see what they wanted.

West they discovered about 7 A.M. a black Brig under British Colors six or seven miles astern which as soon as she saw the Bark began to fire Guns to bring her to, but the Bark continued to course until the Brig came within half a mile of her and then brought to after having had several shots fired at her which passed her - That when the Brig came up alongside she [illegible] hold down the English Colors and hoisted those of Buenos Ayres and some man on board her who spoke good English ordered the Bark to lower her topgallant sail and back her sails and to send a boat on board with the Captain and his papers -they complied with the ordered to back the sails but the Captain answered that he had not a boat on board which could swim, upon which some canister shot from a long gun were fired at them from the Brig which spread fore and aft from the water's edge to the Mast head, whereby a passenger, Thomas Garvey a private of the 16th Regiment was severely wounded, the foretopmast back stays, the foretop gallant back stay, the foretop mast stay, the foretop gallant rigging and the main Royal stay were shot away, and nine shot went through the foretop sail, two in the fore mast, and many shot went into the Starboard side of the Bark and through the Boats, upon which the Bark immediately lowered her Boat and Alexander Mowatt, 2nd Mate, Mr. James Smith, a Passenger, Henry Johnson, Joseph Marlborough and John Barking, seamen, went to the Brig to see what they wanted.

Mowatt and Smith went on the deck of the Brig but the latter's people finding the Captain had not come began to beat them and drove them back into the Boat which returned to the Bark and Smith related what had passed adding that the Captain must go on board with his Papers, and thereupon Mr. Gibbs went with the same Crew taking his papers with him.

Smith remained in the Bark. When the boat got alongside the Brig, the Captain went up the side and the rest of the people in the Boat were ordered up after him. Captain Gibbs (as the Crew of the Boat afterwards reported) laid his papers on the Capstan & immediately one of the Brig's Crew with his cutlass chopped them in two and they wore all ordered down below, but the Captain not going down quick enough, one of the Pirates made a blow at him with his Cutlass and cut off part of his hat.

The pirates then manned the Bark's boat with six men each armed with a brace of Pistols and a Cutlass who came on board the Bark by the larboard gangway and on getting upon the deck began with their Cutlasses to cut away at the people who were looking over the gangway and severely wounded Henry Sales the Carpenter, Edward Morris, an Artilleryman and Daniel Mullane, Patrick Sloane and Henry Donahue, soldiers, which was done in the most wanton manner and without the least provocation and had the affect [sic] of driving them all below except Richard Johns who was at the wheel, and of leaving the Pirates in the possession of the deck. They spoke in a language which Examinant supposed to be Spanish but which he did not understand and they looked like men from the country round Cape Horn about Chili [sic] - they were dressed in a coarse check red and black linen.

After these men had been on board a short time consulting together they stationed themselves at different Hatchways and ordered six of the Bark's Crew to come up on the deck, upon which Examinant, Henry Sales the Carpenter, Patrick Cullen the Cook, Andew Bayerman the Steward, John Vincent, seaman, & Ricd Hood Fletcher a Boy, went up, and the Pirates then in broken English ordered them to set the sails and follow the Brig which they did Richard Johns continuing at the wheel. The Bark following the Brig steered in for the Island and in doing so the Jolly boat got adrift and was lost - while the Bark's people were engaged in navigating her if any one had occasion to pass the Pirates who were posted on the deck the latter struck him a with the flat of their Cutlasses as hard as they were able. When the Bark had got under the Island into smooth water the Pirates cut the topsail halyards and top gallant sheets and let the yards fall, and then they began to plunder the ship.

The Bark's skiff was put out and all the live stock consisting of seven sheep, three goats, five pigs and many turkeys, geese, ducks and fowls were put into her and one Pirate with two soldiers and Fletcher by the Pirate's orders got into the skiff to take her to the Brig but all the Oars having been lost with the Jolly Boat they hailed the Brig and told them there were no oars on board, upon which the Pirates in the Brig lowered their stern boat and sent two of their companions on board the Bark - one of these men looked like an Englishman or a north American, and the other was a short swarthy man resembling a Portugueze - neither of these spoke in English -The skiff with the live stock was then sent away to the Brig with the Crew before mentioned and the two Pirates who had arrived last remained with the five others in the Bark, and of these seven men began to plunder the Cabin and store-Rooms.

The plunder consisted of 60 or 70 dozen bottles of Madeira Port Sherry and Beer which they put into their own Boat - they also broke open the trunks and stole the Captain's Chronometer, his watch, all his Clothes, a box of letters and papers, the sextant, spy glass, speaking trumpet and the several Watches belonging to the Passengers and all the portable Articles they could find - they also took the ship's Medicine Chest and a great deal of Money which he believes was what Major Logie, one of the Passengers, had to pay his soldiers with -when the Boat was loaded they sent it off to the Brig and then the skiff returned after which they ordered up all the best sails from the forecastle and put as many of them in the skiff as she could carry which were taken on board the Brig. Their own boat then returned which they loaded with the remainder of the plunder amongst which were all the Examinant's charts, seven in number - Examinant requested one of the Pirates who could speak a little English to give him back one of them, but he refused telling him that bye and bye he would have plenty of Charts. They were in the possession of the Bark upwards of twelve hours.

In the course of the day Joseph Marlborough, Henry Johnson and John Larkin were sent back from the Brig to their own ship but the Captain and Mowatt never did return. Upon one occasion of their sending off their plunder to the Brig they compelled Examinant to go with it and on his return he found that most of the soldiers to whom the Pirates had given liquor were drunk and were down in the fore hatchway and after giving Examinant some food the Pirates ordered him down and then they blocked the Hatchway up, leaving, of the Bark's people, on deck only John Larkin, Hector McFadden, a Soldier, and Fletcher, a boy, which three they carried away with them when they quitted the Bark which they did late at night.

In the course of the day Joseph Marlborough, Henry Johnson and John Larkin were sent back from the Brig to their own ship but the Captain and Mowatt never did return. Upon one occasion of their sending off their plunder to the Brig they compelled Examinant to go with it and on his return he found that most of the soldiers to whom the Pirates had given liquor were drunk and were down in the fore hatchway and after giving Examinant some food the Pirates ordered him down and then they blocked the Hatchway up, leaving, of the Bark's people, on deck only John Larkin, Hector McFadden, a Soldier, and Fletcher, a boy, which three they carried away with them when they quitted the Bark which they did late at night.

There were five females on board whom the pirates had put into the Cabin and when the latter had left the Vessel the women gave the people below notice they were gone, and then the people liberated themselves and discovered that the Pirates had bored two holes in the starboard bow from the Coal hole with a view to sink the ship - they also found that all the rigging except the forerigging was cut through, and that the Pirates had cut into the Main Mast and the Tiller, had destroyed the Binnacle, and had carried away two compasses and two Log Glasses.

At daylight the Bark had lost sight of the Brig, and having during the night pumped out the ship which owing to the scuttling had made about 6 feet of water, they turned to and in a few days rigged her and continued their voyage home -but they very soon discovered that owing to the wetting of a Cargo of Coffee which they had below it had heated and nearly set fire to the ship so that they were under the necessity of heaving overboard about 200 Bags of Coffee.

Examinant having remained on the Bark's deck nearly the whole day and overlooked from the starboard side forward the loading of the Boats and the proceedings of the Pirates had ample opportunity of observing the persons of the eight who were all that came on board the Bark and he is quite certain he should recognize every one of them if brought in view of them, and that he should be able to point them out amongst numbers as well as to identify many of the Articles stolen by the Pirates -he cannot undertake to say he should recognize any others of the Pirate's Crew the number of whom he understood from Mr. Smith was about seventy. -

1st August 1828

Andrew Beyerman States - That he was steward of the "Morning Star" - he confirms generally the statements of Mr. Bushby and in addition thereto says that understanding the Spanish and Portuguese and as well as French (his native language) he had an opportunity of observing and hearing the discourse which passed amongst the Pirates who boarded the ship. That of these eight Pirates four were Frenchmen, two were Spaniards, and two Portugueze, and there was a ninth man who did not come aboard but sate [sic] in the Pirates's Boat whom from his appearance Beyerman took to be an Englishman. This man never uttered a word but held his head down as if he wished to avoid notice. Beyerman is sure that he should recognize every one of these nine men were he to see them - Two of the Frenchmen were addressed by their companions by the names of Nicolas and George and one of the Spaniards who appeared to have the command of those who boarded was called Pepe which signifies Joe. At one time they held a consultation whether they should sink the ship, set her on Fire, or murder all on board. The Pirate Brig carried five Guns on each side and a long eighteen-pounder amidships.

He refers to the annexed printed Paper, as containing a detail furnished by him of the proceedings of the Pirates, the facts of which he is ready to verify.

[hand written comment at top of page: Statement of Andrew Beyerman the Steward of the Morning Star]

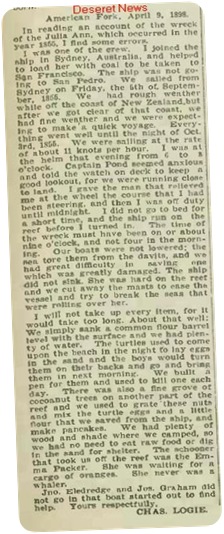

THE MORNING STAR BOARDED BY PIRATES

That crime is awfully increasing on the land in this country, has now become an established and most awful fact; and that it is increasing by piracy on the high seas, is also lamentably true. Bandit's of sea-robbers, collected from all countries, and living by plunder and robbery on the ocean, are almost daily to be met with now, as the sea is covered with so many millions of property. When will merchants see their true interests, by aiming to diffuse abroad religious instruction among seamen, and encouraging the labors of the British and Foreign Seamen's Friend Society, if it were only for the protection of their own property, and the preservation of human life? The following has been brought to us by the Steward of the Morning Star, who has attended the Mariners' Church. Songs and papers concerning it our now hawking about the streets; and the Steward wishes a correct statement should go before the public through the medium of the New Sailor's Magazine. Christians, pray and labor for the salvation of perishing sailors.

Authentic Account of Piratical Proceedings on Board of the Bark MORNING STAR, on the 19th of February, 1828, off the Island of Ascension.

At day-light saw the Island of Ascension, bearing W. distant about six leagues. Saw a brig on the larboard tack [note this has been corrected by hand from "starboard"], about six or eight miles distance on the larboard bow [note this has been corrected by hand from "starboard"]: she stood on the same tack, until we brought her abaft the beam, when she wore, and made sail, got in our wake, and stood after us, apparently in chase. At seven o'clock, she fired a gun, and hoisted a blue British ensign.

We then hoisted our colors, and continued our course under a press of sail, Capt. Gibbs suspecting, from the appearance of the brig, that she was a pirate. At eight A.M. the brig coming up with us very fast, fired two more guns, to bring us to. Capt. Gibbs not willing to shorten sail, she then fired a shot which passed close under our stern. This not having the desired effect, she fired a second shot, which fell close to our starboard quarter. Capt. Gibbs then gave orders to shorten sail, which, having been done, she soon ranged up, with a pistol-shot on our starboard beam, fired a gun unshotted, hauled down her British ensign, and hoisted a Buenos Ayres one; blue, white, blue, horizontal. Capt. Gibbs hailed the brig, to know what they wanted; when he was answered in English, "Why did you not heave too when we fired the first gun? I am a Columbian. [sic] Lower your top-gallant sails, and send a boat on board."

The top-gallant sails were lowered immediately, and Capt. Gibbs answered, that he had no boat that could swim. The pirate then, without hailing again, fired a gun, mounted on a pivot, amidships, loaded with canister shot, which did considerable damage, wounding severely one man, and cutting the sails and rigging, as the shot scattered from the quarter of the ship to the forepart of her, several of which lodged in the side of the ship, foremast, long-boat, and water-casks. Capt. Gibbs, then gave orders for the jolly-boat that was over the stern to be lowered; and dispatched Mr. James Smyth, passenger, Mr. Alexander Mowat, second mate, and three seamen.

As soon as the boat got alongside of the pirate, and Mr. Smyth had gone on board, they ordered two men to come out of the boat, and enquired if Mr. Smyth was the captain, and had the ship's papers. They answering in the negative, the pirates began beating them cruelty with the flat of their swords, ordering them to return to the ship, and send the captain {2} with the ship's papers. The captain accordingly took the papers, and went on board with the same crew in the boat. As soon as he got on board, the savages cut the hat off his head with a cutlass, took the papers out of his hands, put them on the capstan, cuts them up in inch pieces, and threw them overboard.

They then ordered the men out of the boat, and drove them and the captain below, and fastened the hatches over them. They then manned the boat with six men, the stoutest and the most savage-determined amongst them. They were each armed with two pistols, a cutlass, and long knives. Their boarding we could not oppose, having no arms on board, and the brig lying on our weather-beam, within pistol-shot, and her guns loaded and pointed. She appeared to carry five guns aside, and the long pivot-gun above-mentioned, an 18-pounder.

As soon as they boarded, with their cutlasses they began beating and cutting the invalid soldiers, women, and children, who had all collected about the gangway to see them come on board, uttering dreadful oaths in Spanish, and driving them below, wounding severely four soldiers. They then placed sentries on the hatches, and turned the rest of the sailors on deck, to brace the yards up on the larboard tack, and make sail to run the ship under the south-east end of the island, so that they should not be seen from the north-east end where the garrison is; all the time beating the sailors fore and aft of the ship with their cutlasses, pointing their long knives to their bosoms, and threatening to stab them.

The ship going about six knots, the jolly-boat, which was towing under water along-side of the ship, was cut away by the order of one of these savages, that seemed to have command over the rest. He was a Spaniard, [marginal note: Pepe] and stood about six feet. About this time, the carpenter got a severe cut with a saber on the left shoulder; and although the man's blood was running in profusion, its did not stop those savages from beating him with the flat of their swords: when they had run the ship close enough under the land, they hove her to, cutting away all the halyards. They then allowed some of the invalids to come on deck, to assist in hoisting the skiff over the side, for the purpose of transshipping goods from the ship.

They then commenced plundering her of sails, cordage, canvas, and all sorts of stores that they could lay hands on; all the captain's live stock, and the medicine chest; all the captain's wine, spirits, and all they could get at; breaking open the store-rooms, lockers, &c.; plundering the passengers and others of their most valuable clothes, money, jewels, watches, &c. They then broke open the hatches to get to the wine belonging to the cargo, which, however, they could not effect, its being stowed under the provisions and water-casks.

They then the collected the captain's trunks, and after having broken them open, in hopes to find his money and plate, they carried them off, with all his charts, nautical instruments, barometer, chronometer, &c. One of the ruffians [marginal note: Nicola] put a pistol to the steward's ear, but luckily for the man, it missed fire, swearing in French that he would shoot him, as he would not disclose where the captain's property was hid. He then re-primed his pistol, and was going to try again, when he was checked by one of his comrades, who told him that he was too ready with his pistol. He then fired it over the side, in order to let him know that it was loaded with ball. In the evening, having done with plundering, and having made the sailors and soldiers almost intoxicated, they drove all the males on board down in the fore hatch, with the exception of the two apprentices, and one soldier, of the 78th Highlanders, who were in the boat.

They then sent all the women into the cabin. They secured the fore-hatch, and kept a {3} sentinel over it, leaving them entirely ignorant of each other's fate. About two o'clock A.M. of the 20th, the women not being confined below, two of them ventured up, and found the pirates had quitted the ship. They then searched, and found that the men were confined in the fore-hatch. They then gave information that the pirates were gone, and, with great exertion, they extricated themselves from their confinement. When they got upon deck, to the consternation of everyone, they found that they had kept the captain, the second mate, the two apprentices, and the soldier. They had cut the whole of the mizen rigging; all but three shrouds of the main rigging; and all of the main top-mast back stays.

They had also cut with an adze about four inches in the main-mast, seven feet above the deck; half through the tiller, shattered the wheel and binnacle; and taken away the skiff, compasses, log glasses, &c. The well was sounded, when it was found that there were six feet and a half of water in the hold. Upon examination, it was found that the pirates had bored two augur-holes in the starboard bow in the coal-hole, which they have taken the precaution to stop with corks in the lining, to prevent discovery. The leaks were soon stopped; and, with great exertion from every one on board, we succeeded in gaining on the leak.

At day-light, the island being in sight about twenty miles to windward, the crew looked well round, in hopes of seeing the skiff; but its being useless, they set the fore-sail, and kept the ship before the wind, until they could secure the main-mast, so as to set sail on the larboard tack.

At nine A.M. set the fore-top-sail. Wind S.E. steering W.N.W. having providentially found an old spare compass and a chart, that had escaped the pirates' searches.

N.B. the eight men that were on board plundering were, four Frenchman, two Spaniards, and two Portuguese, as the steward of the ship asserts; he being master of both French and Spanish languages, and knowing the difference of the Spanish and Portuguese.

The two sailors [marginal note: H Johnson & Joseph Mellor now at sea] that were confined on board of the pirate with the captain, and that were sent back about three o'clock, state that there were a good many Englishmen on board of the brig, and that they were very much ill-treated by them, when they drove them out of the boat, and back into her.

The wounded were as follows: Thomas Garvey, private soldier of the 16th Foot, invalid, received a canister shot, which perforated the thick of his thigh. Edward Morris, of the Royal Artillery, a severe cut with a saber across the back of his right-hand, one cut on his head, and one on the middle of his back. Patrick Donoghue, of the 83d Foot, a severe cut on the cranium, one on the left arm, and one on the left shoulder. This man, in consequence of his wounds, was given up, not expecting that he would survive; but by the exertions of the surgeon, Mr Johnstone, he got over it. Patrick Sloane, 83d Foot, a severe cut of a saber, diagonally from the wrist-bone of the right arm, to within two or three inches of the bend of the arm. Daniel Malone, of the 16th Foot, a slight cut of a saber, on the right shoulder. Henry Sales, carpenter of the ship, a severe cut with a saber on the left shoulder, from which a piece of bone was extracted. This man suffered a great deal, and fell in a violent fever, in consequence of his loss of blood, as the wounded was not dressed for twenty hours after it had been inflicted.

On the 20th of February, after the larboard main and mizen shrouds were spliced, and the masts secured, sufficiently to carry sail on the larboard tack, the chief officer, Mr. George Bushby, gave orders to steer {4} to the westward for Pernambuco, on the coast of Brazil, it being the nearest port, and not having on board a sufficiency of provisions.

On the ensuing morning, Mr. B. consulted Major Logie and Mr. Smyth, passengers, thinking that we had better shape our course towards England, as the Brazilian coast was infested, or likely to be, with pirates as bad as those we had just escaped. Upon examination, he found that there was a sufficient quantity of water on board for fifty days, at the rate of three quarts per man, and there was no doubt of meeting some outward-bound ship, as we should be in their track in a few days, and we might obtain a supply of provisions. Mr. B. therefore called the remaining few of the crew together, and having represented the imprudence of proceeding for Pernambuco, we unanimously determined to suffer what privations should be necessary to bring the ship home to the owners; consequently we resumed our former course, and kept the ship's head to the northward, having only four sailors to do the different duties of the ship, and repair the damages that the standing and running rigging had sustained from those cruel savages.

On the 22d of February, the soldiers reported that a great heat was coming up the four hatchway in their berths, and that the ship was either on fire, or in danger of being so. We ran to open the hatch, and to hoist on deck the upper part of the cargo, which consisted of coffee and cinnamon. Our remaining few sailors, and those of the invalids who were able to exert themselves, commenced hoisting the upper tiers of cinnamon and coffee, where we found that four or five tiers of coffee, which was stowed on a dunnage of ebony, nearly three feet in height, were entirely spoiled, and had so much swollen, that it caused a great pressure of the upper tiers against the beams of the ship.

The heat of the hold was so intense from wet coffee and pepper, that it was impossible for a man to remain down above ten minutes at a time. Notwithstanding all these obstacles, with exertion, perseverance, and the blessing of God, we succeeded, in five or six days, in clearing away most of the damaged cargo; and, with the assistance of Divine Providence, we made our ship sea-worthy again, and pursued our course towards Great Britain until the 13th of March, when it is pleased the Lord to send to our assistance the humane and benevolent Captain Magnus Johnson, of the ship Guilford, on his return from China.

He expressed his gratitude and thankfulness to the Almighty for having put it in his power to relieve us, and with the greatest readiness and pleasure he supplied as with provisions of divers kinds, sails, cordage, live stock, a chronometer, nautical instruments, and, in fact, everything that we stood in need of. He allowed two of his best sailors to join us, to assist in navigating the ship to London, which port, with the help of God, we reached on the 18th of April, being two months after our encounter with the pirates. Such, Rev. Sir, is, without exaggeration, the authentic account.

A BEYERMAN

The bark, Morning Star, sailed from Ceylon on the 13th Dec. 1827, bound for London, with the following passengers, viz. Major W. Logie 97th Foot; Mrs. Logie and child; Hospital Assistance, J. Johnstone, in charge of invalids; Mr. J. Smyth, merchant; Mr. William Robinson, ordnance department; F Goodwin, surgeon, 1st Royals; seventeen invalid soldiers, from his Majesty's 16th, 97th, 83rd,and 78th Foot; four women, and nine children.

Missing when the crew got possession of the ship again: -Captain Thomas Gibbs, master; Mr. Alex. Mowat, second mate; John Larkin and R. Hood Fletcher, apprentices; and Hector M'Phadden, 78th Highlanders.”

THE LOGIES – LATER YEARS

The Logie’s eventually retired from the military and the family moved to Canada where they were extremely prosperous and prominent members of the community.

The oldest surviving children stayed in Scotland. The younger children moved to Canada with their parents. One son was a judge. Another was a sheriff. Grandsons were decorated military officers.

Not long ago, stories of Pirates almost seemed to be fairy tales from days gone by but no more. Now we read of current day pirates attacking unprotected ships off the coasts of of most of the continents of the world . It seems that society is sliding back down the scale of civilization.